Google is Working Hard to Confuse You

Online search expert Benjamin Edelman has documented how Google’s changes to its interface serve to further confuse its users and generate more revenue.

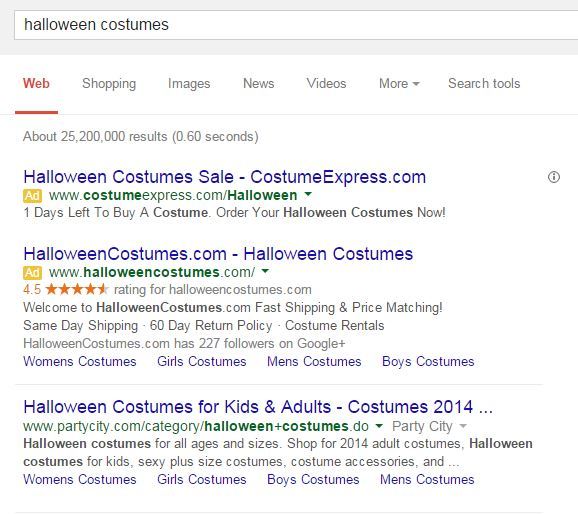

Google’s Advertisement Labeling in 2014

While FTC guidelines call for “clear” and “prominent” visual cues to separate advertisements from algorithmic results, Google has moved in the opposite direction — eliminating distinctive colors that previously helped distinguish advertisements from other search results. Intuition and available data indicate that users find this change confusing — contrary to longstanding practice, and less clear than the alternative. This change increases advertisement clicks and hence increases Google’s revenue, but Google offers no countervailing public benefits for this approach.

–Benjamin Edelman – October 13, 2014

Example

Why Does this Matter to You?

Google is driving users to click on advertisements that are less relevant to their searches and are potentially more dangerous — all because it means more $$$$$ for Google.

The Impact of Less Prominent Advertising LabelsThe elimination of distinctive advertisement background colors makes it significantly easier to confuse advertisements with algorithmic results. Examining the change, Moz.com remarked that without a background color, “the ads look more like organic results.”

Separately, Moz praised the yellow “Ad” label that now accompanies advertisements. But that label measures just 22×15 pixels — yielding 330 pixels of distinctive color, whereas historic backgrounds regularly measured thousands or even tens of thousands of square pixels.

Google widely touts the importance of A/B testing to measure the effect of a change to site design. But consider impact of A/B testing on disclosures that reduce advertisement clicks. If a change makes the disclosures smaller or less prominent, it will tend to increase advertisement clicks — which A/B testing would count as an improvement. In contrast, longstanding legal obligations that the disclosures must be provided and, indeed, must be “clear and conspicuous” — even if, as appears likely, such disclosures reduce advertisement clicks.

In an August 2014 article, Groupon Director of Product Management Gene McKenna assessed the impact of Google’s changing presentation format on paid advertising clicks. McKenna reports that, under Google’s prior format (including a distinctive background color for top-of-page ads), Groupon received approximately 15% more clicks on algorithmic results than on paid results. But after Google removed the background color on top-of-page advertisements, paid clicks jumped sharply — at one point 75% more paid clicks than algorithmic clicks, roughly double the paid clicks Groupon received previously.

McKenna points out that paid advertisements tend to be less relevant than algorithmic results. (My research is in accord. For example, in the third chapter of my Ph.D. dissertation, I found that paid advertisements were nearly twice as likely to fail SiteAdvisor’s safety metrics (testing for adware, viruses, spam, and links to other unsafe sites, among other problems) as were algorithmic results for the same search terms.) By diverting users from high-quality algorithmic results to lower-quality advertisements, Google sends users to less useful destinations.

An equally troubling outcome is that Google’s advertisements send users to the same sites they were already trying to reach. For example, if a user searches for Groupon, McKenna’s research indicates the user is now more likely to click a paid ad to Groupon, whereas in the past the user would often click a no-cost algorithmic link. That’s a transfer of wealth from advertisers to Google. Given Google’s $60+ billion of cash, it’s hard to see how this makes the world a better place.

McKenna finds that the effect of Google’s format change ultimately wears off: Three months after implementation, most users had nearly reverted to their prior behavior of skipping over Google’s prominent top-of-page ads. But the effect remains notable and, to my eye, worrisome. For one, consider the users too busy or naive to notice — users who, to this day, will succumb to less relevant advertising and will continue to drive up advertisers’ costs. Furthermore, the three-month period is harmful in its own right. Google changes page format often. If every change yields a several-month period where users are confused and advertisers’ expenses increase, that’s a large fraction of the time when outcomes are needlessly poor. Rather than celebrate the ultimate diminution of the problem, we should bemoan three months of bad outcomes as three months too long.